Within radical black feminism, the project to accurately identify and name our communities, our identities, and our dominators has been one way to combat nomenclature used to “deny the story, obscure injustice, and disguise power” (Sell). Depending from what vantage point one is viewing, the name “Feminist” can serve as a proxy for a list of other designations. “Feminazi,” dyke, man hater, and race traitor are just some of the epithets that “Feminist” can draw.

Exactly what is a radical black feminist?

Is she radical by virtue of being feminist? Put simply, the answer is Radical Black Feminism and radical black feminists are intersectional. First named “interlocking” by the foundational Combahee Collective, intersectionality finds its modern roots in their manifesto. The beginnings of intersectional thought are distilled succinctly when they write, “The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face.” The evolution of radical black feminist thought can be traced via its historic trajectory in the U. S., which extends before the Combahee Collective’s statement, and up until the present time. Finally, radical black feminism is a political stance that does specific work in two places.

The first is the culture at large, where its practitioners strive to educate all women identified persons and every other gender that to be feminist is to be human. The cultural work also includes a continual re-centering of the discourse around feminism toward intersectionality, as well as the radical work of self-care.

The academy is the second arena where radical black feminism strives to maintain black women’s studies departments that engage in robust and community concerned scholarship. That scholarship includes recovering black women’s archival stories and expanding to include diaspora studies. Like two trains running, radical black feminism works in the culture and in the Academy to further its goal of dismantling heterosexism, patriarchy, capitalism, and white supremacy.

The grandmother of black feminism is Anna Julia Cooper and the “grand text” of radical black feminism is a Voice from the South. Her phrase “when and where I enter” provides the title for Paula Giddings’ foundational book. She is quoted in bell hooks’ Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism and no discussion of radical black feminism can begin without her. When Cooper wrote, “Only the Black Woman can say “when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me”(31). Cooper is saying that when the water rises, all ships rise as well. She was the first to write her belief that the condition of Black women is the harbinger and test of the condition of the whole race. Unfortunately, Cooper is also one of the first feminist thinkers to put the dangerous idea of the moral superiority of women into play. In Voice (after relating a story of a woman’s cruelty toward a Chinese man), Cooper goes on to explain that the woman was only acting “like a man” (51). It seems that Cooper believed in the inherent goodness of the oppressed. She seemed think that women were naturally moral and needed only to be brought into “equality” with men in order to be recognized as such.

Equality is a naming that was detrimental from the beginning, because it does not trouble systemic bias; Equality merely begs for the chance be equally as biased as the current system.

As is often the case, however, one need only look to black women’s literature find a response to Cooper’s gendered essentialism. Toni Morrison has made it her mission two expose the monstrous and amoral in women. I would submit there isn’t one lead female character in any Morrison novel which any woman would want to be. Morrison’s inherent lesson is that unkindness lives in the hearts of men and women. Morrison avoids the impulse to only reclaim “Negro greats” or historical figures that represent “The best of the race.” Early in her ground breaking novel Beloved, the characters Baby Suggs and Sethe have the following exchange: “”We could move,” she suggested once to her mother-in-law. “What’d be the point?” asked Baby Suggs. “Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief. We lucky this ghost is a baby. My husband’s spirit was to come back in here? or yours? Don’t talk to me. You lucky. You got three left.” (2-3). Morrison metaphorically asserts that black women must deal and go through the labor of purging ghosts from the past, even the ones that reflect badly on us.

Before Morrison, however, a member of the New Negro Renaissance also considered the culpability of black women in not just acts of unkindness, but in collusion with the dominating system of patriarchy. Nella Larson’s novel Quicksand explores the pervasive and “quicksand” like resignation of Helga, who finds herself in a marriage to a man she does not love, and overwhelmed by mothering 4 young children, along with maintaining the petite bourgeoisie appearance that being the wife of a preacher requires. Helga tries to find comraderie with other women in her community.

“but” protested Helga “I’m always so tired and half a sick. this can’t be natural.” “Laws Chile we’s all ti’ed an ah reckons we’s all gwine a be ti’ed til kingdom comes. Jes make the bes of it honey jes make the best yuh can.”(279)

Helga finds out the women envy her position and are surprised by her complaints. Larson make an astute observation via this scene, but it is not without its problems. One must wonder why the use of dialect was necessary. In this context the complacency and collusion of these women is also seen as tied to a lack of education. It can be extended to a false syllogism ending with the conclusion that feminist thought cannot be contained in poor communities. As the conversation within feminist circles complicated over time, the concerns of cultural elitism and gendered essentialism were added to the cadre of problematics that continue to be studied.

Black radical feminism also endured the growing pains of a generational shift. The discourse moved from challenging the Jim Crow system to questioning an even larger system of bias. Playwright Lorraine Hansberry names this generational schism via her character Mrs. Younger when she says:

“In my time we was worried about not being lynched and getting to the North if we could and how to stay alive and still have a pinch of dignity too . . . Now here come you and Beneatha—talking ’bout things we never even thought about hardly, me and your daddy. You ain’t satisfied or proud of nothing we done. I mean that you had a home; that we kept you out of trouble till you was grown; that you don’t have to ride to work on the back of nobody’s streetcar—You my children—but how different we done become”(523)

The post war growing pains exhibited in “A Raisin in the Sun” portended the emergence a much more complex cultural dialogue surrounding feminism. It is out of this generation that bell books was born.

Probably the most famous and most influential of the Feminist theorists, hooks’ trademark naming (“heterosexist/capitalist/white supremacist/patriarchy”) continues to be used today.

On the way to hooks, however, we must return to the Combahee Collective to trace the events that led to the solidifying of intersectionality as a rallying cry. The Collective observed, “It was our experience and disillusionment within these liberation movements, as well as experience on the periphery of the white male left, that led to the need to develop a politics that was anti-racist, unlike those of white women, and anti-sexist, unlike those of Black and white men.” This postwar generation of female thinkers began to notice that the labor movement, the Communist Party, the beats, even (and especially) Black nationalism, all marginalized black women according to race or gender. Hooks, who goes back and pieces together black women’s feminist history since their arrival on U. S. shores, draws a connection that pulls together a concise timeline of the deliberate deployment of patriarchy. Moving from history to popular culture, hooks observes, “Negative images of black women in television . . . are not simply impressed upon the psyches of white males, they affect all Americans. Black mothers and fathers constantly complain that television lowers the self-confidence and self esteem of black girls. Even on television commercials the black female child is rarely visible—largely because sexist-racist Americans tend to see the black male as the representative of the black race” (6). Hooks also pioneers what has become part and parcel of Black radical feminist cultural critique. Among the first to look at it cultural products like television programs as driving engines for systemic bias, hooks made some insightful and some reductive assessments of the place of the black woman’s image in popular culture. The work of the Combahee Collective and bell hooks served to legitimize feminism as a body of scholarship and to solidify its place in the Academy. Now, the community work and the scholarship could both be mined for the social justice aims of Black radical feminism.

As Black radical feminism came into its own in the cultural arena, it’s three aims were:

(1) to remove the gendered and raced requirement of being for being a Black radical feminist and open it to all genders and races, (2) to make sure that the conversation about feminism remained intersectional, and finally (3) to promote an atmosphere of radical self-care for women identified persons.

Regarding the first aim, Barbara Smith writes in “Racism and Women’s Studies, “Let me make quite clear at this point, before going any further, something you must understand. White women don’t work on racism to do a favor for someone else, solely’ to benefit Third World women. You have to comprehend how racism distorts and lessens your own lives as white women — that racism affects your chances for survival, too, and that it is very definitely your issue. Until you understand this, no fundamental change will come about” (49). Where hooks named White women’s complicity in the domination of black women, she left no workable actions one might take in order to become accomplices in the dismantling of gender prejudice. Barbara Smith offers an entry into action-orientated dialogue between black women and white women. In When and Where I Enter, Paula Giddings uses a series of essays to parse the relationships between black men and black women. Giddings looks at the sexism in the black liberation movement of the 60s and the devastating effect that the acceptance of the Moynahan report had on the psychic conception of family in the black community. Giddings begins a conversation that continues till this day about whether the work of feminism can be completed if men never identify as feminist.

To this point she writes, “The concrete reality of the Black situation does suggest, however, that most of the required revisionist thinking must be done by men. Historically, racial necessity has made Black women redefine the notion of womanhood to integrate the concepts of work, achievement, and independence into their role as women. On the male side of the coin, if abandoning a family, or suppressing that feminine spirit (and it is feminine), is considered a male prerogative, then the same necessity compels Black men to redefine man- hood. And women have to help them do it” (352).

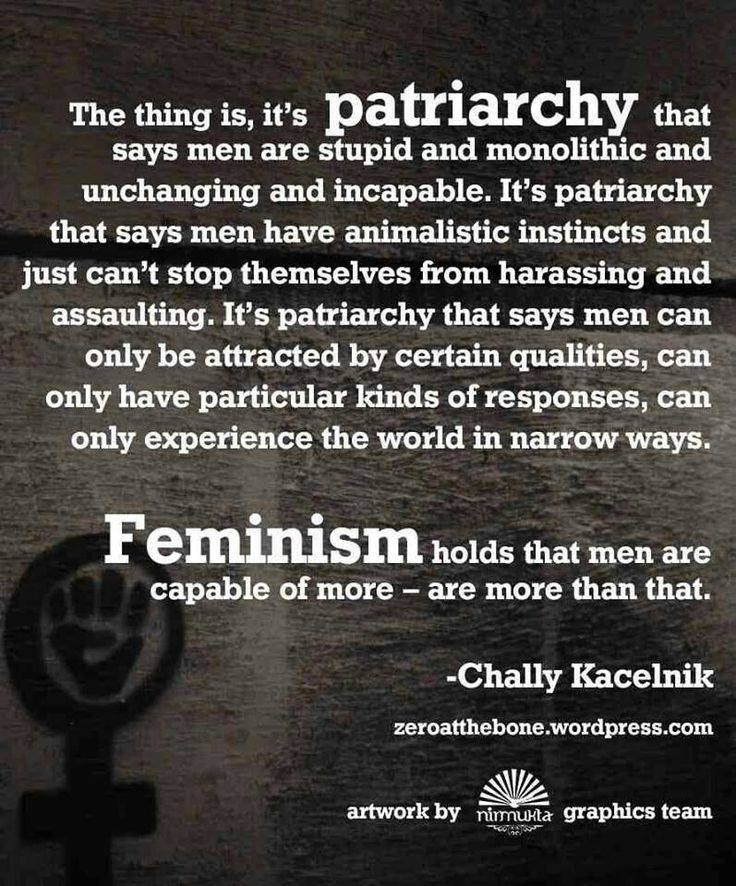

Giddings’ assessment that black women have to “help” black men redefine manhood is problematic, to say the least. Everyone has her own work to do, and this is why a constant re-centering of the discourse in feminism must be engaged. Like all systems of dominance, patriarchy seeks to subtly make its privileged group the locus of power and push others toward the margins. Contained within the foundational anthology This Bridge Called my Back, is a poem titled “The Bridge Poem” by Kate Rushin. The following stanza cogently speaks to this point:

I explain my mother to my father my father to my little sister

My little sister to my brother my brother to the white feminists

The white feminists to the Black church folks the Black church folks To the ex-hippies the ex-hippies to the Black separatists the

Black separatists to the artists the artists to my friends’ parents . . . (xxii)

“The Bridge Poem” explores a phenomenon in which people of color are expected to explain other marginalized groups to the dominant group. Being assigned this work in the culture removes the responsibility for naming whiteness and exploring how it dominates the cultural discourse for white people. Rushin goes on to affirm her responsibility to herself and portended the naming of ”Self-care.” To follow that line of reasoning, in “The Uses of the Erotic,” Audre Lorde deeply queries what she names “the erotic,” and makes a compelling case for “self-care as a radical act.” Her assertion that the erotic is a “deeply feminine” power and as such, is feared, goes a long way to connect patriarchy to a kind of femmephobia.

Lorde’s essay pulls together Giddings’ directive that black women be responsible for black men’s gendered work, and Rushin’s complaint of being assigned the “bridge work” and turns them on their ear when she writes,

“As women, we have come to distrust that power which rises from our deepest and nonrational knowledge. We have been warned against it all our lives by the male world, which values this depth of feeling enough to keep women around in order to exercise it in the service of men, but which fears this same depth too much to examine the possibilities of it within themselves. So women are maintained at a distant/inferior position to be psychically milked, much the same way ants maintain colonies of aphids to provide a life-giving substance for their masters” (54).

Lorde’s naming of the erotic provides a path for healing that must be engaged when doing the cultural work of Black radical feminism. Many of the black women who created Black radical feminism’s founding scholarship are now deceased. Barbara Christian and Audre Lorde are both gone, while many of their white contemporaries are still with us. Both women found the academy a place at war with self-care, and because the work in the academy is so important, Black radical feminism looks for techniques to assure survival within the institution.

In the introduction to All the Women are White, All the Men are Black, But Some of Us are Brave, Gloria T. Hull writes this assessment of Black Women’s Studies’ entry into the academy:

The inception of Black women’s studies can be directly traced to three significant political movements of the twentieth century. These are the struggles for Black liberation and women’s liberation, which themselves fostered the growth of Black and women’s studies, and the more recent Black feminist movement, which is just beginning to show its strength. Black feminism has made a space for Black women’s studies to exist and, through its commitment to all Black women, will provide the basis for its survival”(xx).

Although Hull writes glowingly about this exciting time, and the development of these departments did have a “legitimizing” effect on the field, the academy can also have some marked negative effects as well. One of the most insidious is named by Barbara Christian in “The Race for Theory,” and can be explained as the devolvement into what they believed was a Derrida-esque theory for theory’s sake. Christian pointedly observes,

“some of our most daring and potentially radical critics (and by our I mean black, women, third world) have been influenced, even coopted, into speaking a language and defining their discussion in terms alien to and opposed to our needs and orientation”(52).

That being said, the academy has also resulted in much robust critical scholarship, and priceless archival work recovering the narratives of black women not previously considered by the academy. Toni Morrison’s “Playing in the Dark” is one such example of the sort of groundbreaking critical work that feminist writers and scholars can produce. Morrison parses why “ Black and colored people or symbolic figurations of the blackness are markers for the . . . benevolent and the wicked; the spiritual… and the voluptuous;”sinful world but delicious sensuality coupled with demand for purity and restraint. These figures takes shape, form patterns, and play…” (ix). Alice Walker, whose reclamation of Zora Neale Hurston’s work and legacy, provides another example of the ways the academy can serve Black radical feminism. In “In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens,” Walker queries,

“How they did it: those millions of Black women who were not Phillis Wheatley, or Lucy Terry or Frances Harper or Zora Hurston or Nella Larsen or Bessie Smith-nor Elizabeth Catlett, nor Katherine Dunham, either-brings me to the title of this essay, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” which is a personal account that is yet shared, by all of us. I found, while thinking about the far-reaching world of the creative Black woman” (70).

Walker and Morrison both contributed mightily to the space of cultural criticism that was reinvigorated by bell hooks. On one hand, Morrison parses the way white culture retells itself the same stories using the trope of black versus white. Morrison further asserts that the very concept of whiteness find his genesis in opposition to an overwhelming and threatening blackness. On the other hand, Walker moves away from the totalizing idea of dark versus light, and drills down to the particularly insidious removal of black women’s artistic outlets as a mechanism of patriarchy. Nearing the last decade of The 20th Century the academy also saw the addition of African Diasporic Studies with an emphasis on global feminisms. South Africa’s struggle with apartheid brought Bessie Head into the perview of U. S. Black radical feminist scholars. Head’s novel, A Question of Power, speaks not just to the complicating factor of mixed race parentage, but to the intersecting ideas of Nation and revolution. Radical black feminism began to further complicate intersectionality when it acknowledged that Black radical feminism coalesced globally around issues of slavery, colonialism, and, in present times, neocolonialism. To add, because Head’s novel focuses on a main character who slowly slides into “lunacy,” her novel also helped to make space for the addition of “ability” to the identities that were to be named as comrade designations in the fight against the global heterosexist, patriarchal, white supremacist, capitalist system. While A Question of Power grapples with the trauma of colonization, Tsi Tsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions troubles how African cultures move into gender consciousness in a post-colonial landscape. The diaspora represents an exciting “fattening” of the Black radical feminist canon, and its addition to the previous scholarship and archival work make the academy a place where intersectionality is authentically practiced.

To my mind, the vanguard of black radical feminism’s scholarly work is being done in the sphere of gender, queer, and lesbian studies. The excellent Book by L. H. Stallings, Mutha’is Half a Word: Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular, Myth, and Queerness in Black Female Culture troubles the culture of orality and vernacular in queer black communities. It brings into contestation the ways “black male femininity” represented in the bodies of gay and queer black men, and “lesbian masculinities” break the gender binary inherent in a sexist system. Stallings is also reversing the trend of the “tyranny of the essay.” She uses lesbian poetry to assert her thesis that the vernacular language used in poor and working class lesbian community represents a revolutionary, coalition building cultural production. Stallings writes “Poetry has always been an important part of Black vernacular culture, and in Black female culture it becomes a genre very capable of translating desire through various trickster mechanisms” (33). Stallings’ connections bring fresh ideas to the tropes of Africanisms like the trickster figure when applied to queer theory. Stallings’ innovative scholarship bring me to my final point. The vanguard of black radical feminism’s cultural work is being done as we speak in response to the signature issue of the policing and the brutalization of black bodies. In This Bridge Called my Back, Cherie Moraga writes,

The train is abruptly stopped. A white man in jeans and tee shirt breaks into the car I’m in, throws a Black kid up against the door, handcuffs him and carries him away. The train moves on. The day before, a 14-year-old Black boy was shot in the head by a white cop. And, the summer is getting hotter. I hear there are some women in this town plotting a lesbian revolution. What does this mean about the boy shot in the head is what I want to know. 1 am a lesbian. I want a movement that helps me make some sense of the trip from Watertown to Roxbury, from white to Black. (xiv)

Resonant with today’s terrifying list of young black and brown people who have not survived police interactions, Moraga’s observations prove there continues to be a missing piece of the conversation that names why the perpetrators of police violence are mostly male, and why the victims are mostly male. Work is being done in the present day to expose the way gender and power to create an over reliance on violence in men. At the same time, a lot work is been done to expose the numbers of women brutalized by partners and by the racist system of policing in the U.S. Finally Black radical feminism resonant area has to resist the urge to fall into old patriarchal modes centering men in the role of the most cherished loss at the expense of women who are also facing brutality.

Works Cited

Christian, Barbara. “The Race for Theory.” The Nature and Context of Minority Discourse, ed. Abdul JanMohamed and David Lloyd. Oxford University Press: New York, 1991. Print.

Christian, Barbara. “Images of Black Women in Afro American Literature: From Stereotype to Character.” Black Feminist Criticism: Perspectives on Black Women Writers. New York: Pergamon, 1985. Print.

The Combahee River Collective. The Combahee Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizing in the Seventies and Eighties. Albany: Kitchen Table Press, 1986. Print.

Cooper, Anna Julia. A Voice from the South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. Print.

Dangerambge, Tsitsi. Nervous Conditions. London: The Women’s Press, 1988. Print.

Davis, Angela Yvonne. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude” Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Random House, 1999. Print.

Giddings, Paula. When and Where I Enter. New York: Bantam Books, 1985. Print.

Hansberry, Lorraine. A Raisin in the Sun. New York: Vintage; Rep Rei edition, 2004. Print.

Head, Bessie. A Question of Power. New York: Longman, 2009. Print.

Hooks, Bell. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Boston: South End Press, 1981. Print.

Hull, Gloria T., Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith, eds. But Some of Us Are Brave: All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men: Black Women’s Studies. New York: Feminist Press at CUNY, 1982. Print.

Larsen, Nella. Quicksand. Mineola: Dover, 2006. Print.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. New York: Random House LLC, 2012. Print.

Moraga, Cherríe, ed. This Bridge Called my Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Watertown: Persephone Press, 1981. Print.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York: Vintage, 2004. Print

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark. New York: Random House LLC, 2007. Print.

Stallings, L. H. Mutha’is Half a Word: Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular, Myth, and Queerness in Black Female Culture. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2007. Print.

Walker, Alice. In Search of our Mother’s Gardens. New York: Harcourt, 1983. Print.