Hint: Harriet Ball was her name, and she passed away in 2011. A veteran teacher from Texas, Ball was observed in the early 90s by two novice teachers, two young white men who were impressed by the way she infused the curriculum with rhythm and mnemonics that engaged the children thoroughly; much more thoroughly than they had been able to do.

Those two men, Mike Feinberg and Dave Levin, have never denied the origins of their program. But here I sit two and a half decades later wondering if Harriet Ball, who taught for 35 years in the Houston and Austin school districts, knew what the KIPP program became.

Answer: Black and Brown women. Like so much cultural production in the U.S., the Knowledge is Power Program, or KIPP as it is commonly known, was conceived by the genius and love of a black woman.

I enrolled my son in the KIPP charter school when he began 5th grade. I took him out before his 8th grade year ended when we were able to move to a suburban neighborhood with good public schools.

I was slightly familiar with KIPP because I had read poetry at a KIPP Academy in Memphis, Tennessee. So when I saw that there was one in St. Louis, Missouri, I expressed an interest and sent in my son’s application. I was heartened when two representatives from the school showed up at my home to talk with me about the program and to have my son and I sign a contract. The contract was designed to impress the seriousness of academics upon us both and to make it clear to me that they expected rigorous parental involvement.

I happily signed the contract and looked forward to sending my son to a school where rigor was the order of the day.

And I have to say, the curriculum was quite rigorous. Each week, my son came home with a packet for each subject. My son still uses the multiplication facts song he learned there, and the accountability he was taught when it came to behavior and completing assignments are others areas of positivity I could point to.

So why is it that when I think of his time enrolled at KIPP I am left with a persistent and a worrisome sadness?

The sadness begins with black and brown women. Like so much cultural production created in the U.S. the Knowledge is Power Program, or KIPP as it is commonly known, relies on the genius and love of black and brown women.

It is black women and brown women who submit their children to joyless, punitive school that (1) turn school into drudgery, (2) rely on the artistic and rhythmic propensity privileged in black and brown children’s cultures, but removes it (almost) entirely from the curriculum, and (3) rely on the militaristic and institutional behavior model that in my gut I believe is a “raced” response to education.

The Drudge Report

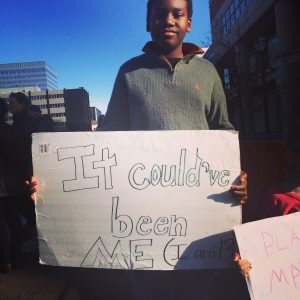

My son’s time was dominated with school. And the model relied on young teachers who did not yet have parenting obligations on their plate. I would daresay it relies on teachers who have no other real commitments. The faculty was there at sunrise and often did not leave until nightfall. And then there was school on Saturdays. And school in the summer. The signal, of course, was that there were no safe leisure activities in the communities we came from. This seemed to support that very American suspiciousness of bodies at leisure, especially if the body is not white. What were Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Tamir Rice doing anyway? Shouldn’t they have been at somebody’s job? Or somewhere creating something for someone?

Joyless

My son’s school had arts classes on Saturdays. There was also a visual art class as part of the curriculum during the week. The middle school I attended 30 years earlier had art, choir, and band during the week, integrated into the curriculum. My high school had all those and dance. By contrast, at my son’s school, the arts were positioned as very special treats for children. One thing the arts do is introduce play into the atmosphere. But, of course, black and brown children have played enough, right? The arts are frivolous and don’t create income. The arts are for delicate sensibilities not the rock hard pragmatic labor sensibilities of black and brown people. Black and brown people have relied too much on entertaining and should engage in more serious pursuits. This all goes with the mistaken belief that the arts don’t support academics, and don’t tap into a valuable kind of intelligence.

Another Brick in the Wall

I began my career as a public school educator at the point when the uniform trend swept through our nation’s public schools, and we’ve seen no steady uptick in test scores or graduation rate to coincide with bland uninspired clothing. Of course, my son’s school had a uniform policy. Students were also expected to read a book as they walked in line from one class to another. At first glance it seems that to require students to read as they walk in the hall is a good idea but so is teaching students to interact in kind and productive ways. To have spontaneous conversation. To share ideas. To know that a disagreement doesn’t have to be total. These are all valuable social assets that black and brown bodies are not treated to very often.

The bottom line is this: We want our sons and daughters to live. The brutalization of black and brown bodies that has entered the national conversation in the last few years has been in the minds, hearts, and consciousness of black and brown mothers for quite some time. And here is a population of mothers looking for some way, anyway to save our children. We are ripe for the picking because we feel (and rightly so) that we are in an emergency. But what do we sacrifice? We sacrifice joy, we sacrifice play, we sacrifice hijinks, shenanigans, and pranks. We sacrifice childhood.

A Mississippi native, Treasure Shields Redmond is a published poet, master educator, community arts organizer, and successful entrepreneur. Treasure was raised in the federal housing projects, and went on to be signed to M.C. Hammer’s label as a hip hop artist, and writer. She is the author of chop: a collection of kwansabas for fannie lou hamer (2015). Her doctoral research focuses on the recorded performances of foundational Black Women poets, and the ways they deployed sound to impact the canon and justice movements. Treasure centers collaboration in her personal arts practice and as an organizing principle. As such, she has co-founded a funding collective for Black artists called The Black Skillet, and a podcast that centers voices of color called Who Raised You? Treasure is the founder of Feminine Pronoun Consultants, LLC, and Get The Acceptance Letter Academy. To read, hear, support, or hire Treasure, go to any of the following: www.FemininePronoun.com, www.GetTheAcceptanceLetter.online, www.blackskilletfunders.tumblr.com, and www.whoraisedyoupodcast.com